Journalism has long been associated with transparency, neutrality, and public service. Yet across modern history, militant and extremist organizations have repeatedly exploited journalistic identity as a tactical disguise. By posing as reporters or media workers, operatives have accessed restricted spaces, conducted surveillance, and disseminated propaganda under the appearance of legitimate news gathering. This misuse presents severe ethical and security dilemmas because it blurs the boundary between professional reporting and covert political violence (EBSCO, n.d.; UNESCO, 2023).

Although the overwhelming majority of journalists operate in good faith—often at great personal risk—documented incidents demonstrate that press credentials and media equipment have been deliberately weaponized. Such practices place civilians and security forces in danger and simultaneously corrode public trust in journalism. When journalism is manipulated for violent or ideological ends, the legal protections that safeguard independent reporting are weakened (OSCE, 2019; Office of Justice Programs, n.d.).

Historical Precedents

One of the earliest and most infamous examples of journalistic cover being exploited occurred during the 1972 Munich Olympic Games. Members of the Black September organization reportedly used press credentials to enter the Olympic Village, taking advantage of the relatively unrestricted movement granted to media personnel. This access facilitated their attack on Israeli athletes and demonstrated how journalistic openness could be converted into operational vulnerability (EBSCO, n.d.; Office of Justice Programs, n.d.).

Similar strategies appeared during the conflict in Northern Ireland. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, certain Irish Republican Army (IRA) members allegedly presented themselves as reporters in order to observe security routines, transport materials, and identify potential targets. Because journalists were perceived as neutral actors, they could move between communities and checkpoints with less suspicion than ordinary civilians (Office of Justice Programs, n.d.).

These cases established a model that later organizations would refine: using media identity not only to gain physical access but also to control narratives surrounding violence.

Contemporary Manifestations

In the twenty-first century, terrorist groups have integrated media production directly into their operational structures. Al-Qaeda and later ISIS developed sophisticated propaganda networks that merged battlefield activity with visual documentation. Fighters in Syria and Iraq frequently posed as journalists while filming executions and attacks, distributing this material globally for recruitment and intimidation purposes (ICCT, 2023).

At the same time, these operatives collected intelligence on troop movements and infrastructure while benefiting from assumptions that journalists were protected noncombatants. Cameras became both symbolic and functional weapons, serving psychological warfare objectives while masking reconnaissance activity (UNESCO, 2023).

Hezbollah has also been associated with individuals holding press passes who were later accused of monitoring Israeli military positions in Lebanon. Again, the mobility and legitimacy attached to journalism enabled activities that would otherwise have drawn immediate scrutiny (EBSCO, n.d.; ICCT, 2023).

Hamas has developed one of the most elaborate media systems among militant organizations, operating outlets such as Al-Aqsa TV and employing freelance photographers and videographers closely aligned with its political and military objectives. After the attacks of October 7, 2023, investigations and media reports suggested that some individuals affiliated with Hamas’s military wing presented themselves as journalists while filming and transmitting footage of the assaults for propaganda use (ICCT, 2023; OSCE, 2019). This convergence of violence and media production collapsed the distinction between documentation and participation in hostilities.

Strategic Logic and Methods

Militant organizations favor journalistic disguise for several reasons:

- It lowers suspicion in politically sensitive locations.

- It enables access to conflict zones, checkpoints, and public events.

- It grants narrative influence by shaping how violence is interpreted globally.

Press vests, cameras, and credentials provide visual camouflage among legitimate reporters, particularly in chaotic war environments. However, the tactic also generates long-term harm by fostering distrust toward independent journalists. Governments respond with stricter regulations and accreditation processes, which can restrict genuine reporting and undermine press freedom (UNESCO, 2023; OSCE, 2019).

In the digital age, media and violence have become inseparable components of extremist strategy. Attacks are increasingly designed as spectacles for online consumption, blending ideology with instant broadcasting (Mitnik, n.d.; Wikipedia, 2025).

Spillover Effects: Radical Activism and Journalistic Identity

The normalization of journalism as a shield for ideological activity has not remained confined to terrorist groups. Elements of radical political activism in Western democracies have adopted similar postures by identifying as “citizen journalists” while engaging in disruptive or unlawful behavior at protests, religious services, and political events.

Such incidents illustrate how the claim of journalistic purpose can be used to justify intrusion into protected civic or religious spaces, reframing activism as reporting. This trend reflects a broader cultural shift in which professional identity is leveraged to avoid scrutiny or accountability.

Public controversies involving prominent media figures have further complicated this dynamic.

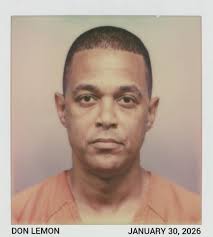

Don Lemon’s Arrest

The issue with Don Lemon and the FACE Act (Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances Act) centers on his recent federal indictment in late January 2026.

As an independent journalist, Lemon was arrested after covering and livestreaming an anti-ICE protest at Cities Church in St. Paul, Minnesota, on January 18, 2026, where demonstrators disrupted a worship service to confront a pastor reportedly employed by ICE amid immigration enforcement tensions.

A federal grand jury indicted Lemon along with eight others—including another journalist—on charges of conspiracy to deprive individuals of their civil rights (under 18 U.S.C. § 241) and violating the FACE Act (18 U.S.C. § 248) by allegedly injuring, intimidating, or interfering with religious freedom at a place of worship.

Originally enacted in 1994 to protect access to abortion clinics from obstruction or threats, the FACE Act also safeguards religious exercise at houses of worship from similar interference using force, threats, or obstruction.

Prosecutors under the Trump administration argue Lemon’s presence and actions—such as questioning the pastor in close proximity and coordinating with protesters—crossed into criminal interference rather than protected journalism, while critics, press freedom advocates like FIRE and outlets including The Intercept, call it an overreach and politically motivated weaponization of the law to chill dissent and reporting on immigration protests.

Lemon said: “I’ve been pleasantly surprised to see the community coming together.” (Link:https://x.com/EricLDaugh/status/2017273187629740121?s=20)

He also said: “After we do this operation, you’ll see it live.”

(Link: https://x.com/JoshWalkos/status/2017330848266068070?s=20)

Lemon, released without bond after his initial court appearance in Los Angeles, has vowed to fight the charges as a First Amendment battle, with his next hearing set for February 9 in Minneapolis; the case remains ongoing and has ignited debate over press protections versus enforcement of religious freedom laws.

Of course, while no determination equated this with terrorism, the episode highlighted how professional status can blur legal boundaries and obscure transparency.

This phenomenon demonstrates how strategies pioneered by militant groups can be imitated by ideologically motivated actors seeking legitimacy and protection. Although the moral and legal gap between terrorism and activism is vast, the shared tactic of weaponizing professional identity weakens public confidence in journalism as a neutral institution.

Countermeasures

In response, both governments and journalistic organizations have strengthened verification and accreditation procedures. High-risk events now rely on layered credentialing systems, and international bodies warn reporters about impersonation threats (UNESCO, 2023).

Security agencies increasingly scrutinize dual-use technologies such as cameras and drones in sensitive areas. Some states prohibit civilians from wearing military-style gear or press markings in active conflict zones. Despite these efforts, journalism remains vulnerable to exploitation because it is protected by international humanitarian law and democratic constitutions (OSCE, 2019).

Balancing security with press freedom has therefore become one of the central challenges of counterterrorism policy.

Conclusion

From Black September and the IRA to ISIS, Hezbollah, and Hamas, the misuse of journalism as operational cover reveals a consistent pattern: media identity provides access, legitimacy, and narrative authority. These practices facilitate violence while simultaneously damaging the credibility of independent reporting.

The influence of this tactic now extends beyond terrorism into radical political activism, where journalistic claims are sometimes used to avoid accountability for disruptive conduct. As a result, the press faces a growing crisis of trust and increasing pressure from legal systems to distinguish genuine reporting from ideological performance.

Safeguarding journalism requires confronting its misuse without undermining its essential democratic role. Only by reinforcing ethical boundaries and transparent standards can societies preserve both security and freedom of expression.

References

EBSCO. (n.d.). Terrorism and news media: Overview.

ICCT (International Centre for Counter-Terrorism). (2023). Prevention of the (ab)use of mass media by terrorists.

Mitnik, Z. (n.d.). Post-9/11 media coverage of terrorism. City University of New York.

Office of Justice Programs. (n.d.). Media and terrorism.

OSCE. (2019). Guidelines for reporting on violent extremism and terrorism.

UNESCO. (2023). Media and the coverage of terrorism: Manual for trainers and journalists.

Wikipedia. (2025). Terrorism and social media.

Written with the help of AI. Photo is Don Lemon’s mugshot.

You must be logged in to post a comment.